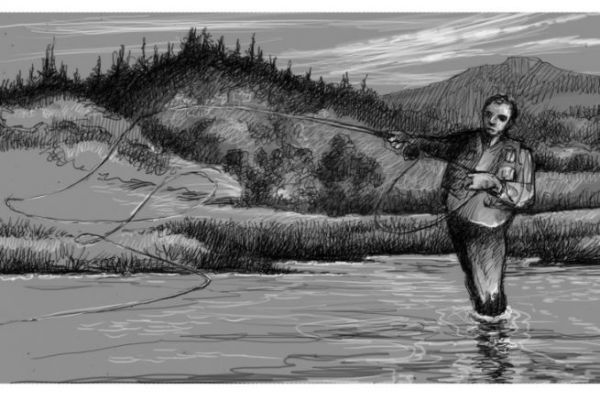

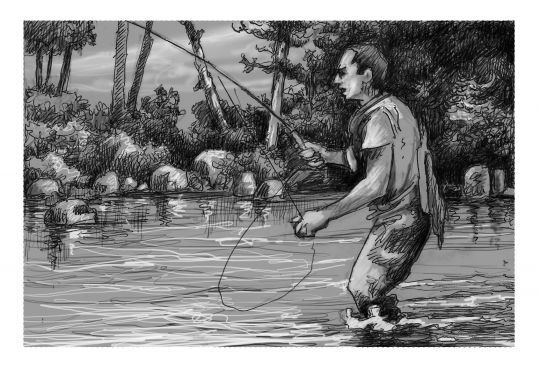

The fly fisherman's gesture

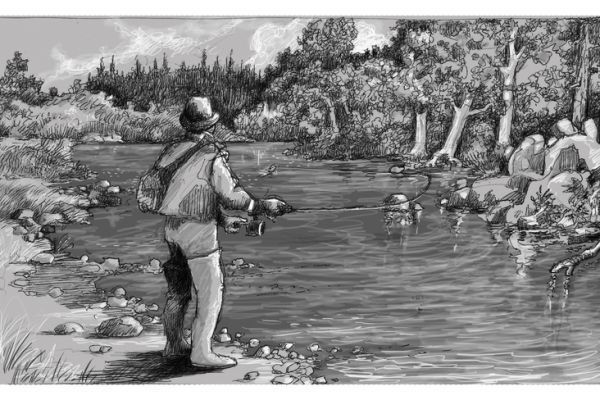

Artificial fly fishing is all about the gesture. Artistic in scope, millimetric in precision, sometimes supple, sometimes scathing, but always elegant. Gone are the milling of the fixed drum, the throw under the rod, the dislocated [1]grip, gestures found in other types of fishing. Here, all is finesse and sensation, all tends towards a majestic curve. The fly-fisherman's rod, the whip, that noble tool which, with the right thinning of the strap, makes the toupee snap above the mane of wild beasts or horses, demands an immutable gesture from the practitioner. From the soft snatch to the straight lunge, everything depends on the cadence and blocking of the silk's path. As with the violinist's bow, the hold and amplitude of the movements must be perfectly mastered to lead the fly, that treacherous feathered hook, to its aquatic target.

An august gesture! As for learning how to do it, a guide, an initiator or an experienced instructor seem essential to get the job done a hundred times over. And thousands of times, the fly on the currents or riffles.

First steps on the fly

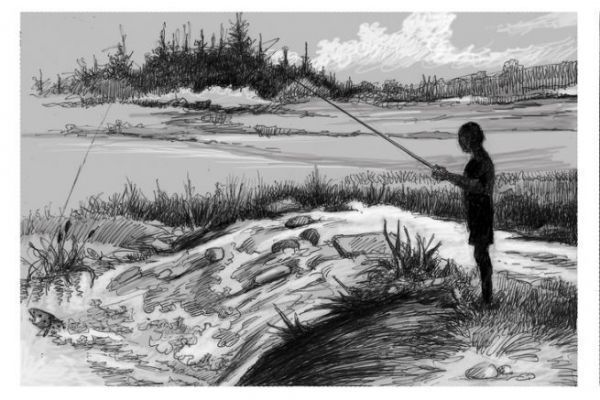

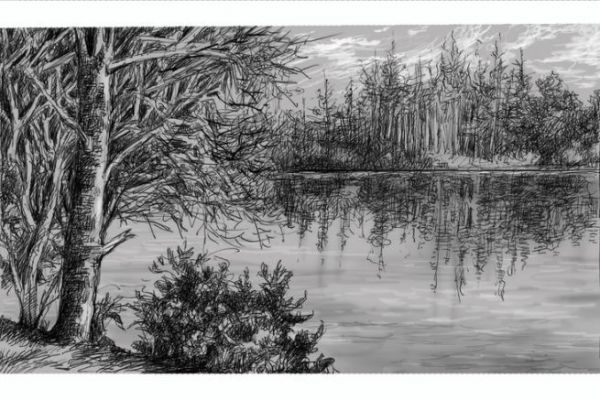

I took my first steps as a fly fisherman at the age of twenty, at a time when only feathered hats were allowed. Indeed, fishing fashion was all about pheasant trimmings, preferably taken from the neck of a golden male or a Lady Amherst. With their elegantly adorned headgear, they could be seen unfurling their split bamboo rods on the pristine waters of the Haute-Loire, département 43. Sometimes, as I met them on the banks of the Lignon or Dunière rivers, I would discreetly spy on them, my gaze admiring and envious.

My cousin and I, childhood teammates along the streams, decided to take the plunge the day fiberglass fly rods arrived in France. Thus were relegated to the status of decorative relics the costly Pezon et Michel foils, which we used to sell in the shop windows of Manufrance in St-Etienne.

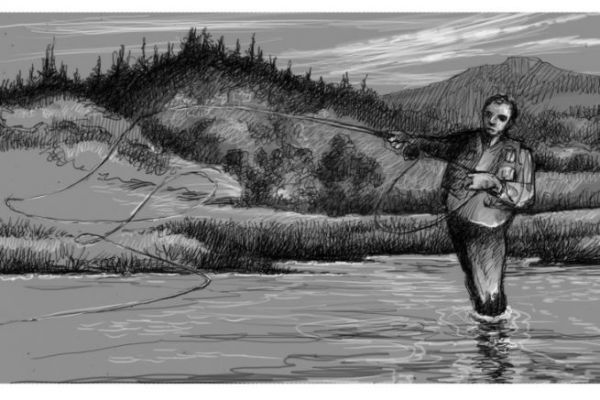

An arduous apprenticeship

With Pierre Popoff's initiatory manual in hand, the apprenticeship was laborious. The conolon fly rods were good, perhaps too soft. The fly line and leader curled awkwardly in the air. Getting the fly to land delicately at the end of the line was essentially a matter of gesture: in this respect, the whimsical rotations we conceded to our wrists proved very detrimental. The attitude recommended by Pierre Popoff, in the A.B.C. de la pêche à la mouche, published by Bornemann in 1967, contributed in its own way to the randomness of the cast: "... elbow glued, without stiffness, to the body..." Discomfort and inaccuracy to boot!

On the meadow or on the duck pond, it was rare for the fly to land correctly at the end of the leader. The first imitations, fashioned from darning cotton, were coarse and shaggy, and could not withstand the snapping of the silk. This was followed by a river debut punctuated by numerous snags and copious nylon tangles. We lined up many disappointing, even exasperating fishing trips.

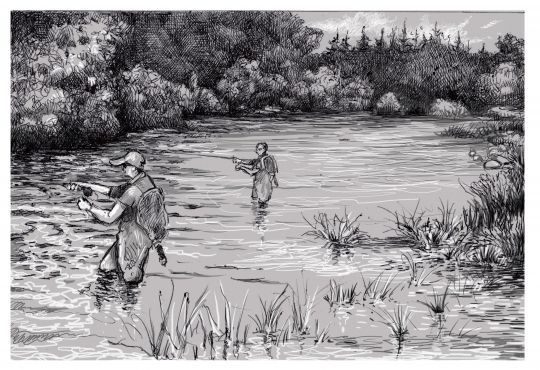

Great fun at the water's edge

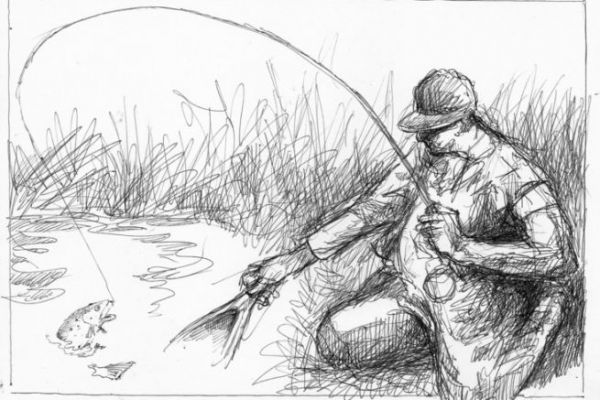

However, one day, one fine spring morning, after yet another landing on a very classic slick, a pretty, compassionate trout came to pick my red-bodied spider, right there, almost at my feet.

Was that enough to validate my learning? Not at all, since fifty years later, after decades of practice, my gesture still deserves to be improved.

But I continue to leaf through Pierre Popoff's pages, thanking the author for the clarity of much of his advice. And I readily admit that he was right when he wrote that last paragraph:

"I hope it will be the beginning of a long series of great joys on the water. "