How does a fish "hear"?

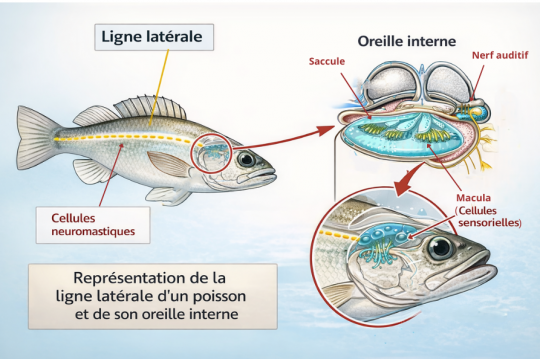

Unlike terrestrial mammals, fish have no visible ears and do not perceive sound solely as an airborne sound wave translated by an eardrum. Their perception relies on two complementary sensory systems: the inner ear and the lateral line.

The inner ear detects variations in sound pressure, mainly at low frequencies. In some species, it is reinforced by bony structures (such as the Weber's apparatus in cyprinids) that amplify signal transmission.

But it's above all the lateral line that plays a fundamental role. This sensory organ, composed of receptor organs (neuromasts) distributed along the body, picks up micro-vibrations in the water, slow movements, turbulence and hydrodynamic disturbances. In other words, fish don't just "hear": they physically feel their immediate environment.

This is a key point in understanding the impact of motors and sounders: a signal can be inaudible to humans, yet perfectly detectable to fish.

Frequencies and vibrations: what our equipment really produces

The front electric motor

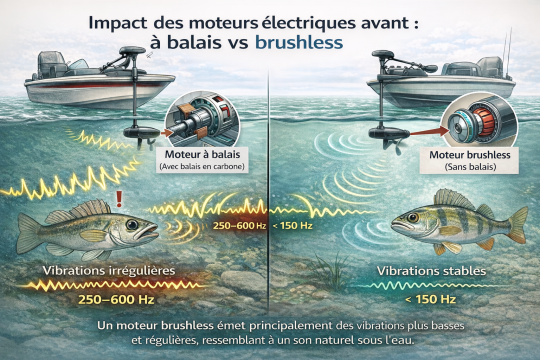

An electric fishing motor generates mainly low frequencies, usually below 200 Hz, but accompanied by regular vibrations due to propeller rotation and electromagnetic pulses up to 600 Hz. This signal is continuous and localized under the boat, particularly when using Spot-Lock.

Motor technology influences this vibration signature: brushed motors produce more irregular vibrations, while brushless motors, thanks to their smoother rotation, emit more stable, linear low frequencies. These frequencies correspond precisely to the zone of maximum sensitivity of many freshwater species. Even at low intensity, the artificial regularity of this signal allows fish to identify it as unnatural when maintained over time.

The echo sounder

Most modern echo sounders operate between 50 and 200 kHz for conventional sonar, and up to 800â?¬1200 kHz for Live or Down Imaging technologies.

These frequencies are well beyond the direct hearing capacity of fish. On the other hand, each impulse generates a sudden variation in pressure, repeated dozens of times per second. So it's not the "sound" that is perceived, but the abnormal mechanical repetition of these impulses, especially when the boat remains stationary above a station.

Different sensitivities for different species

Not all fish react in the same way to acoustic and vibratory disturbances. Their ecology, hunting habits and habitat strongly influence their sensitivity.

Pike-perch (Sander lucioperca)

Pike-perch are particularly sensitive to low frequencies and slow vibrations, typically between 20 and 200 Hz, with peak sensitivity around 80 to 150 Hz. An opportunistic predator, often posted or suspended, it relies heavily on fine sensory perception to detect its prey.

In heavily fished environments, they are highly sensitive to slow, continuous vibrations, and many observations concur: pike-perch remain present under the boat, visible on the depth sounder, but become much less active when the electric motor is running continuously. This is not necessarily an escape, but a prolonged state of alert that inhibits feeding.

Perch (Perca fluviatilis)

Perch are more tolerant, with a slightly wider perceptual range than pike-perch, from approximately 30 to 500 Hz, with good sensitivity in the 100âeuros300 Hz range, particularly when hunting in shoals. However, large single fish show a heightened distrust of repeated disturbances. Sudden variations in motor speed or jerky movements are often more disturbing than the noise itself.

With natural drift, perch return to active hunting behavior more quickly.

Pike (Esox lucius)

Pike perceive mainly very low frequencies, often below 150âeuros200 Hz, and are particularly reactive to sudden variations rather than stable noise.

Its lateral line plays a major role: it is more sensitive to changes in water pressure and displacement than to sound per se. A stable electric motor will often have little effect on a fish already posted, but permanent micro-corrections or abrupt movements can cause a behavioural stall.

In the case of educated pike, the combination of motor and active sonar seems to reduce the time spent on a station.

Catfish (Silurus glanis)

Catfish are sensitive to very low frequencies (10âeuros150 Hz, peak 40âeuros100 Hz) and slow vibrations thanks to their highly developed lateral line. A nocturnal, benthic predator, it often remains postured and uses these perceptions to detect its prey.

In heavily fished areas or under electric motors, its hunting activity may be reduced by a prolonged state of vigilance, without systematic flight, but may even sometimes arouse its curiosity depending on its mood.

Cyprinids (carp, bream, roach, etc.)

Cyprinids have excellent hearing capacity, thanks to their Weberian bones. They are highly sensitive to low frequencies from around 20 Hz to 1,000âeuros3,000 Hz, with excellent sensitivity in the 50âeuros500 Hz range. and to repeated vibrations. In carp in particular, conditioning is well documented: artificial signals combined with regular fishing pressure quickly become negative cues.

Packaging and fishing pressure: a key factor

Fish are capable of learning. Without even being caught, they can associate certain stimuli with an unfavorable situation. In heavily frequented waters, the combo of electric motor + depth sounder + prolonged hovering becomes a recurrent signal.

This phenomenon does not necessarily lead to mass flight, but rather to a change in behavior: more static fish, more timid attacks, reduced windows of activity.

In this context, we prefer natural drifts, reasoned use of the electric motor, and phases of voluntary equipment shutdown, which often lead to more natural behaviour and better acceptance of lures.

In modern fishing, technology is a tremendous asset. But as is often the case, it's how you use it âeuros, not the tool itself âeuros, that makes the difference.

/

/