Catfish, a demonized natural predator

Reintroduced to France in the 1970s after its post-glacial disappearance, the sheatfish (Silurus glanis) is now a fully-fledged component of major river ecosystems. It has adapted well, becoming an apex predator in environments already disturbed by human activity.

Omnivorous to carnivorous, its diet is extremely opportunistic: whitefish, crayfish, molluscs, amphibians, aquatic birds, even small mammals and carrion. However, studies show that catfish adapt their diet to local prey abundance. On average, less than 5% of its diet consists of migratory fish, except at points of artificial concentration (such as fish passes), where its predation can be locally more visible, a bias often exaggerated in anti-silure discourses.

Contrary to popular belief, catfish do not hunt frantically: their feeding rhythm is slow and subject to seasonal cycles. It can go several days without feeding, and its growth slows considerably after a certain age. Large individuals even play a regulatory role, notably through cannibalism, limiting overpopulation. In this respect, their mass elimination could paradoxically encourage an explosion of young, more active and voracious catfish.

But does this make it the main cause of the decline in these species?

An awkward silence on professional fishing

"No scientific study to date has confirmed that catfish is the main cause of the decline in migratory fish

Ôeuros Report of the Scientific Council of the National Biodiversity Committee (2023)

"The impact of catfish remains secondary to that of dams, pollution and fishing."

Ôeuros ONEMA (National Office for Water and Aquatic Environments)

Catfish attacks on migratory fish are often observed at fish ladders, narrow artificial passage points. But above all, these attacks highlight a failure: the architecture of poorly designed fishways, which slow down or trap migrants.

While the catfish is being attacked, the figures on human harvesting of migratory species speak for themselves:

- Some 360 professional anglers fish with gear (nets, traps, etc.) on public rivers in mainland France (source OFB).

- Driftnets catch 5 to 15 tonnes of shad annually in estuaries.

- In 2023, the French quota for glass eels (eel fry, a species classed critically endangered ) amounted to 8.5 tonnes in rivers, and 56.5 tonnes at sea.

- In the Loire-Allier basin, an average of just 568 salmon have been counted each year since 2000. The ecological objective set is 2Ôeuros»400 individuals/year. Human pressure is such that less than 25% of the target has been reached (Source: LOGRAMI, 2020).

And yet, these harvests are not only legal, but sometimes subsidized or tolerated in the name of local traditions. In some cases, quotas are even increased by prefectoral decision, against the advice of scientists.

Management hypocrisy?

It's paradoxical to hear certain representatives of the fishing industry claim to be defending migratory species against catfish, when they themselves directly harvest these species, often without distinction or transparency.

We hear about catfish, but it's dams, nets and pollution that have destroyed the spawning grounds. Catfish have simply adapted to a system that was already ruined.

What's more, catfish regulation campaigns are sometimes carried out with disproportionate means (electrofishing, culling, excessive trapping as seen in recent weeks), while their commercial exploitation remains marginal and unstructured. We kill a predator without even knowing whether its elimination will benefit the ecosystem.

It should also be remembered that the largest catfish (often targeted by these regulations) act as natural regulators through intra-species cannibalism, indirectly limiting their own expansion.

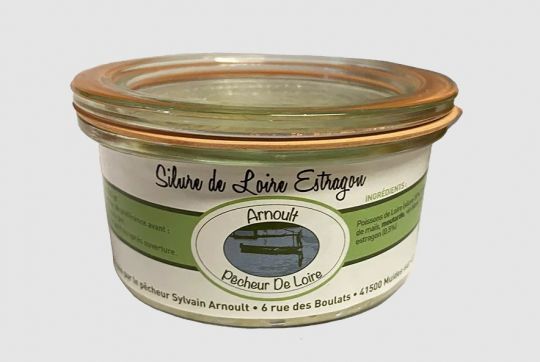

Catfish: a prized product transforming professional fishing

Long ignored in France, catfish is now commercially exploited by many professional fishermen, particularly in the Loire, Rh├?ne, Sa├'ne and Doubs basins. Socio-economic data illustrate this trend:

- Between 2002 and 2009, catches rose from 11.9Ôuros»tonnes to 30.5Ôuros»tonnes of catfish per year, for an estimated value of 182Ôeuros»900Ôeuros»ÔČ.

The average price has stabilized at around 6Ôeuros»ÔČ/kg, varying from one basin to another:

- ~2Ôeuros»ÔČ/kg in Loire-Atlantique,

- ~5Ôeuros»ÔČ/kg on the middle Loire,

- up to 10Ôeuros»ÔČ/kg on the upper Rh├'ne-Sa├'ne, where processors sell ready-to-cook fillets

In the Rh├'ne-Sa├'ne basin, catfish accounts for 55Ôeuros»% of sales for the fisheries whereas in Loire-Atlantique it represented 2.3Ôeuros»% of sales, or around 15Ôeuros»000Ôeuros»ÔČ, and only 0.1Ôeuros»% on the Adour river (source lepecheurprofessionel.fr). But all this could be very different in 2025.

Direct sales practices (boneless fillets) make catfish more readily accepted by the general public, including in the catering trade. Chefs in the Loire region are making the most of it in refined dishes (terrines, carpaccio...). Finally, in basins such as ponds or private circuits, professional fishermen are actively solicited to regulate the population, reinforcing this emerging industry. The economic success of catfish is no longer confined to the exploitation of pests: it has become a structured, fast-growing resource, with its own markets and players (fishermen, fishmongers, chefs) who are transforming a former undesirable into a culinary and economic opportunity.

However, as a large, long-lived, sedentary predator, the wels catfish is particularly exposed to the accumulation of lipophilic pollutants and heavy metals in its body. Studies carried out on major French rivers have revealed significant levels of PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls), dioxins, mercury and cadmium in the flesh of adult catfish... Not very reassuring when you consider that catfish is even served in certain school canteens in mainland France.

Restoring environments rather than finding easy culprits

The current approach is biased: instead of investing in restoring ecological continuity, limiting abstraction or improving fish passes, we prefer to pass the buck to a visible but secondary predator.

The real debate should be about :

- Modernization of fish passes.

- Drastic reduction in commercial fishing quotas for migratory species.

- Elimination of driftnets in sensitive estuaries.

- And rigorous scientific monitoring of populations, including catfish, for decisions based on data, not intuition.

A political diversion

The catfish has become the perfect scapegoat. Its size, hunting behavior and "foreign" nature (although it is now perfectly naturalized) make it an ideal target for masking the failings of French river management.

But the data are clear: anthropogenic pressure (particularly from commercial fishing) weighs far more heavily than any fish, no matter how large.

In this debate, defending catfish does not mean ignoring its impacts. It means refusing to simplify matters, and reminding us that rivers don't need culprits, but rather restoration and political courage.

We can only hope that the FNPF, represented by Mr Claude Roustan, will keep its promises when it declares ┬" │ Á- , ╠euros . [...] ║ ╠╠ ╠euros ╠╠ ╠euros, ╠╠".

/

/